In the accelerating race to control the future of global internet infrastructure, Elon Musk has emerged as the unrivaled emperor of low Earth orbit. While tech giants like Amazon pour billions into their Kuiper project and geopolitical blocs like the European Union and China scramble to create sovereign satellite networks, none have come close to matching the velocity, scale, or geopolitical leverage wielded by Musk’s Starlink.

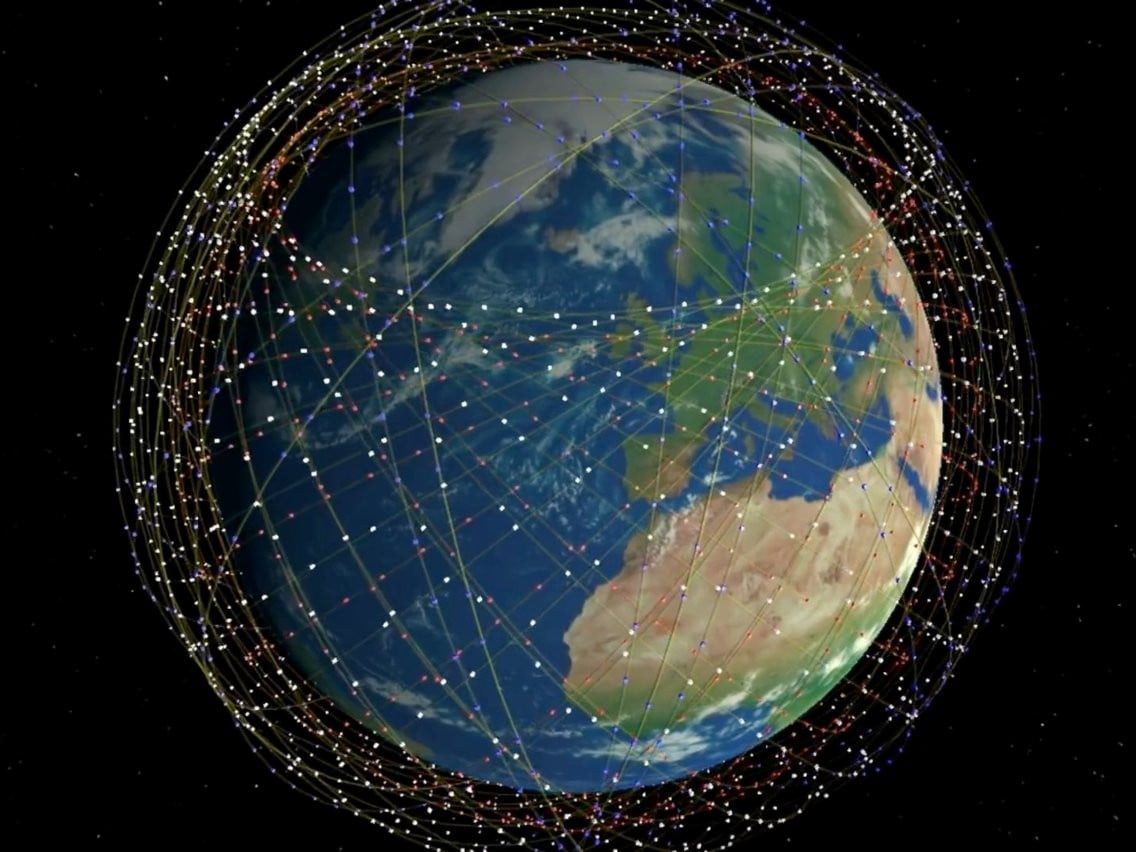

As of mid-2025, with over 7,000 satellites circling the Earth and ambitions to scale to more than 100,000, Musk has turned what began as a side project at SpaceX into one of the most powerful communications backbones in human history.

The original promise of Starlink was simple: deliver high-speed, low-latency internet to remote and underserved regions of the world. But that narrative now feels quaint. In practice, Starlink has become far more than just a connectivity solution—it is a strategic asset, a geopolitical tool, and a technological moat that has put even nation-states on their heels. The Atlantic recently described Starlink as “a new kind of empire,” and it’s hard to disagree.

The world's largest private satellite network is not just an engineering marvel; it is a demonstration of how Musk, a single individual, has eclipsed the capabilities of governments and trillion-dollar corporations alike.

The European Union, recognizing the peril of depending on foreign-controlled infrastructure, announced its own constellation, IRIS², with the goal of ensuring digital sovereignty. But the EU’s project remains in its infancy, beset by bureaucratic delays and funding shortfalls.

The ambition is there, but the execution lags dramatically behind Starlink’s relentless cadence. In the time it has taken the EU to organize committees and secure parliamentary votes, SpaceX has launched hundreds of new satellites, upgraded ground stations, and integrated Starlink into global supply chains.

Amazon, on the other hand, entered the arena with Project Kuiper, backed by over $10 billion and Jeff Bezos’ own rocket company, Blue Origin. However, despite the resources, Kuiper is still in the deployment phase. No real network exists yet.

The earliest meaningful coverage isn’t expected until 2026, giving Musk another full year—at minimum—to fortify his lead. SpaceX, thanks to its Falcon 9 and now Starship systems, can launch hundreds of satellites in a single week, a logistical advantage that Kuiper has yet to replicate due to its dependence on limited launch providers.

China, too, is wary. The Chinese government has long recognized that communications networks are as vital to national security as energy or transportation. But even with its Tiantong and Hongyun systems, China has not been able to create an LEO constellation at the scale or density of Starlink.

Their efforts are also constrained by international distrust, export restrictions, and the geopolitical suspicion that follows any major Chinese tech initiative. More importantly, China’s authoritarian model has hindered its agility in the face of Starlink’s private-sector dynamism.

In sharp contrast, Starlink operates at a breakneck pace and with an autonomy that is borderline dangerous. There is no international oversight. There is no regulatory framework governing LEO dominance.

This vacuum has allowed Musk to act swiftly and unilaterally—such as when he denied or granted internet access in conflict zones like Ukraine and Gaza. Whether one views these moves as humanitarian or manipulative, the implication is the same: Starlink is no longer just a technology platform. It is an instrument of soft power.

Musk has already positioned Starlink as indispensable to the U.S. military, with contracts in place to support everything from battlefield communications to secure drone networks. Starlink terminals have been deployed in war zones, disaster areas, and rural outposts.

The Pentagon has quietly expanded its reliance on Musk’s network, despite the clear discomfort in ceding such strategic infrastructure to a private actor with a history of erratic behavior and political volatility.

Meanwhile, commercial integration is exploding. Airlines, shipping companies, cruise lines, oil rigs, and remote mining operations are all signing on. Starlink has proven that it can operate profitably while scaling, a rare feat in space infrastructure.

Musk’s plan to interlink this network with his upcoming Starship mega-rocket will allow for exponentially cheaper launches and global saturation. If even a fraction of his target—100,000 satellites—is realized, then Starlink will become the single most comprehensive information mesh ever constructed, dwarfing any terrestrial telecoms system.

This dominance is not without criticism. Astronomers have repeatedly warned about the growing problem of light pollution from the ever-expanding satellite constellation. Space environmentalists have raised alarms about orbital debris.

Global regulators are ill-equipped to respond, lacking a unified framework for LEO space. But the truth is, no one can stop Musk right now. The pace at which Starlink is growing means that by the time governments react, the system will be too entrenched to dismantle without causing global disruption.

Even the United Nations has begun informal discussions on “space equity” and the need to prevent LEO monopolies. But these talks are reactive, not proactive. While diplomats meet in Geneva and Brussels, Musk is launching another batch of 60 satellites from Cape Canaveral.

The window to negotiate terms with Starlink as a peer may have already closed. From here on out, it may be a matter of negotiating with Musk as a de facto sovereign actor.

Financially, the implications are staggering. Analysts at Morgan Stanley estimate that Starlink could become a $50–$100 billion asset on its own by the end of the decade.

It not only provides steady cash flow from subscribers, but also underpins future ventures like Mars communications, intercontinental broadband, and high-frequency trading networks. If Amazon and the EU fail to catch up—and all signs indicate they will—then Starlink becomes not just dominant, but hegemonic.

There are precedents in history for corporate empires that outgrew their founding nations: the Dutch East India Company, British Petroleum, even Standard Oil in its prime. But none have ever reached beyond the stratosphere, nor operated on the bandwidth of global consciousness like Starlink. This is not just about market share.

It’s about the very architecture of the digital world—who builds it, who controls it, and who can flip the switch.

If Musk can provide 100% global internet coverage from orbit, while everyone else is still laying fiber cables or testing prototype satellites, then the world has already made its choice—not through democratic vote, but through technological inevitability. And unlike oil or coal or even data centers, there is no alternative network ready to step in if Starlink goes dark.

For now, Musk remains the architect of this invisible empire. The rest of the world is scrambling to catch up, building alliances, forming consortiums, proposing new treaties. But the race may be over. Musk didn’t just win; he changed the terrain, rewrote the rules, and launched the finish line into orbit.

In the words of one anonymous European diplomat quoted in the original Atlantic report: “This isn’t a telecommunications system anymore. This is infrastructure for planetary control.” The sobering truth is, Starlink is no longer a tech story—it is the scaffolding of a new geopolitical reality. And right now, that scaffolding spells one name: Elon Musk.

-1750570235-q80.webp)

-1747889572-q80.webp)

-1749483269-q80.webp)