As geopolitical tensions push multinational corporations to diversify their supply chains and reduce dependency on China, Apple has been at the forefront of efforts to reposition its manufacturing footprint.

With growing scrutiny from the U.S. government, investor pressure to mitigate political risk, and increasing instability in U.S.-China relations, India has emerged as the most often cited alternative.

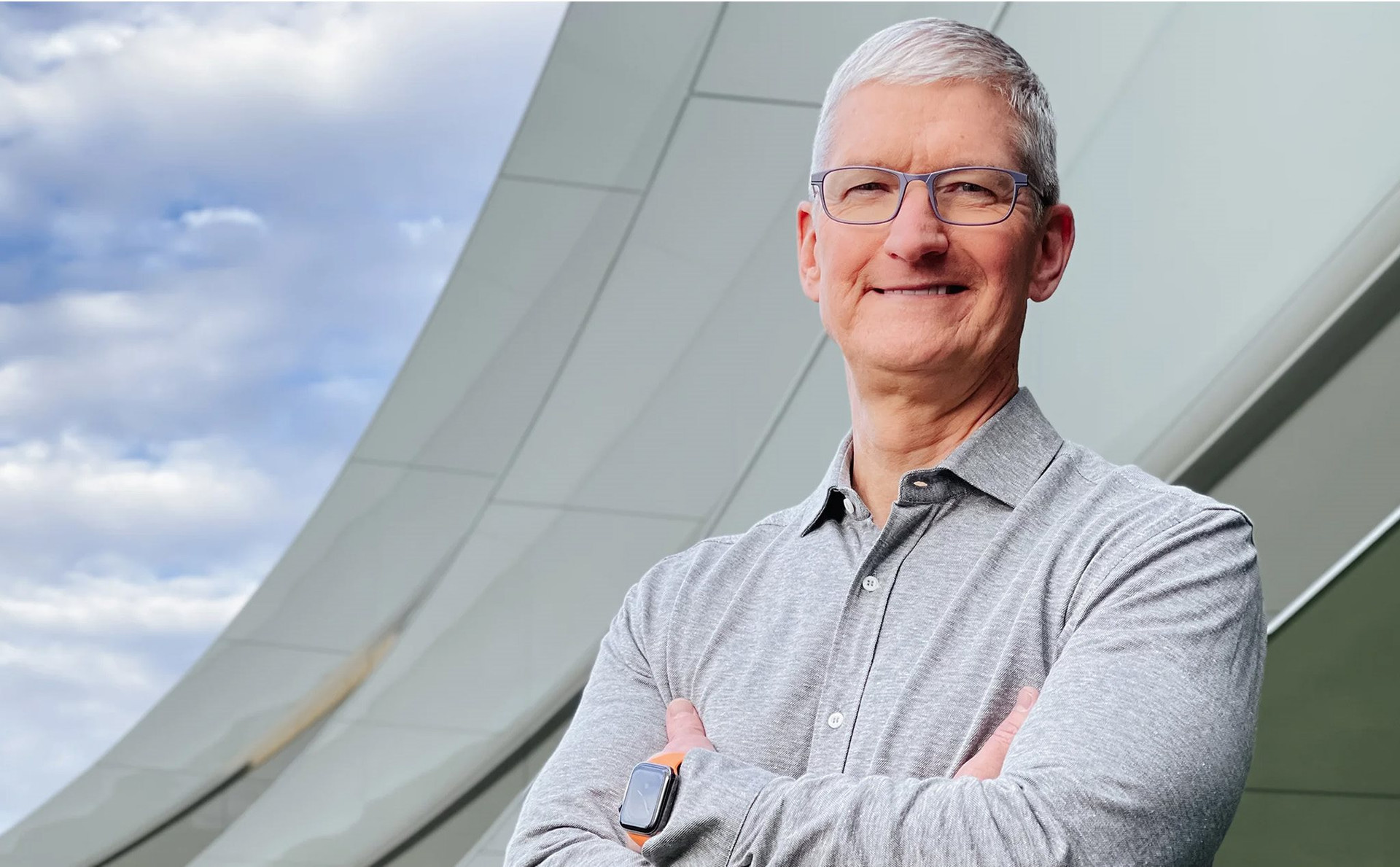

But the reality on the ground is proving more complicated than the rhetoric. Despite high-profile visits, political gestures, and major headlines, India is not ready to replace China as the global manufacturing engine for iPhones. And Tim Cook, while optimistic in public, is fully aware of that fact behind the scenes.

Apple has indeed made tangible moves in India. It has partnered with Foxconn to assemble iPhones in Tamil Nadu, opened its first physical retail stores in Mumbai and Delhi, and announced long-term investment plans.

These efforts signal intent, but the numbers tell a different story. As of 2025, India still produces only a small fraction of Apple’s global iPhone output—nowhere near enough to replace China’s deep and mature manufacturing ecosystem.

Apple may be building phones in India, but it still depends heavily on components sourced from China, which are then shipped to Indian plants for final assembly. This undercuts the narrative of full-scale manufacturing migration and reveals how entrenched China remains in Apple’s supply web.

The challenges are both structural and cultural. China’s dominance in electronics manufacturing is not accidental—it is the product of decades of investment in infrastructure, logistics, human capital, and industrial policy.

Chinese factories operate with military-like efficiency. Their supply chains are hyper-integrated, allowing for just-in-time delivery and rapid scaling. Skilled labor is abundant, and local governments work in lockstep with corporations to facilitate speed and stability.

India, by contrast, is still grappling with inconsistent electricity, underdeveloped transport networks, bureaucratic delays, and a workforce that is still building its competency in high-precision electronics assembly.

Apple’s own internal assessments, leaked in part through supply chain partners, confirm these gaps. Reports indicate that defect rates at Indian assembly plants remain significantly higher than those in Chinese facilities.

Local technicians often lack the specialized training and institutional knowledge that Chinese counterparts have developed over years of handling Apple’s increasingly complex product lines.

Manufacturing an iPhone is not merely about assembly—it involves clean room environments, nanometer precision, real-time quality control, and high-speed adaptation. India is on a learning curve, but it is still years away from reaching the sophistication that Apple demands at scale.

Moreover, cultural dynamics complicate Apple’s operations in India. Labor unions, while less aggressive than in some other countries, have begun to exert pressure on foreign firms to meet local standards.

Language diversity and regional regulatory variations make standardized processes more difficult to implement. Apple’s strict quality control and production cadence don’t always align well with India’s fragmented bureaucratic structures.

These frictions result in slower ramp-up times, inconsistent output, and logistical headaches that Apple’s China operations rarely encounter.

Despite these issues, Apple cannot afford to abandon its India bet. Politically, the move is essential. U.S. lawmakers have increasingly criticized American firms for overreliance on Chinese manufacturing, and Apple’s image has taken hits as a result.

Investing in India provides Apple with a talking point—a way to demonstrate that it is responding to global calls for supply chain diversification. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has embraced Apple as a symbol of India’s rise as a global tech hub.

The opening of Apple’s stores was heavily covered in Indian media and framed as a validation of India’s new economic stature. For both sides, perception matters. But perception is not production.

Apple’s presence in India today is more symbolic than transformative. Yes, more iPhones are being assembled there. Yes, Apple has increased hiring and localized certain supply functions.

But the bulk of the intellectual property, component manufacturing, and logistical command center remains in China. Apple’s suppliers—especially those producing chips, displays, sensors, and batteries—are still overwhelmingly Chinese or China-based.

Shifting this entire ecosystem is not only difficult but also risky. Apple has spent over a decade optimizing its operations in China. Breaking that machine means rebuilding from scratch, something Tim Cook understands all too well.

Cook’s leadership has been defined by operational mastery. He turned Apple into a supply chain powerhouse, managing costs, optimizing logistics, and maintaining impeccable product delivery standards.

He knows that supply chains are not just about geography—they are about reliability, repeatability, and integration. India may be part of Apple’s future, but Cook is unlikely to pretend it can replace China in the near term. In private meetings, he has reportedly cautioned stakeholders about overhyping India’s readiness.

Apple is investing in India not because it can—but because, in a fragile geopolitical climate, it must.

The limitations of India’s manufacturing ecosystem also impact Apple’s broader strategy. Without robust production capabilities, India cannot become a major export hub.

Most of the iPhones assembled in India are sold domestically or to nearby markets. That limits scale advantages and dampens margins. Moreover, inconsistent output quality means Apple must double-inspect products or reroute defective units for rework elsewhere—adding to costs. These inefficiencies would be intolerable if scaled to global production levels.

India’s demographic advantage, often cited as a long-term asset, remains unrealized in the near term. While India boasts a massive youth population and expanding middle class, its per capita income still trails far behind China.

iPhones remain aspirational luxury items for most Indian consumers. Apple’s market share in India remains in single digits, and while rising, it is far from justifying a wholesale supply chain shift. In essence, India is not yet delivering the demand necessary to support the supply Apple needs.

Meanwhile, China is not standing still. Despite political tensions, Chinese local governments continue to invest in infrastructure upgrades, worker training, and factory automation to keep Apple and other firms anchored.

Apple’s largest and most advanced facilities remain in China, and the company continues to benefit from economies of scale there that India cannot replicate anytime soon.

Cook’s balancing act—keeping China operational while expanding in India—is delicate and increasingly difficult, but it is grounded in realism. He knows Apple’s supply chain cannot pivot based on headlines or political pressure alone.

India may one day rival China as a manufacturing superpower, but that day is not today. The road is long, and while Apple is helping pave it, the company’s expectations remain measured.

Tim Cook’s rhetoric may highlight partnership and potential, but his operational decisions reflect caution and incrementalism. Apple’s investments in India are about diversification, not replacement. They are about political optics, not operational overhaul.

In summary, Apple’s expansion into India is a strategic necessity driven by geopolitical currents, not a revolutionary shift in global manufacturing. India offers opportunity, but also constraints.

It is a promising partner, not a proven replacement. Tim Cook knows this, and while the world debates whether India can become the next China, Apple continues to walk a careful line—building for the future while anchored in the present.

For now, India is a hopeful experiment. China is still the engine. And the iPhone, that quintessential global product, remains very much a creation of Chinese precision, not Indian potential.

-1747817252-q80.webp)