In a move that has reignited fierce debates about climate intervention, Bill Gates is reportedly backing a controversial solar geoengineering project aimed at combating global warming by releasing chemical particles into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight.

The project, which involves a Harvard-led team of scientists and is partially funded through Gates’s philanthropic initiatives, centers around a technique known as stratospheric aerosol injection.

By dispersing calcium carbonate or similar reflective compounds into the upper atmosphere, the team hopes to create a thin artificial cloud that can mimic the cooling effects of volcanic eruptions.

While the theory is grounded in well-documented climate science, its implementation on a global scale introduces a new frontier of ethical, environmental, and geopolitical concerns that are as complex as the climate crisis itself.

The idea behind the project stems from natural events such as the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines, which released millions of tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere and temporarily cooled the Earth’s surface by nearly 0.5 degrees Celsius.

Inspired by this phenomenon, scientists have long speculated whether a controlled version of this effect could be harnessed to buy humanity more time in the fight against climate change.

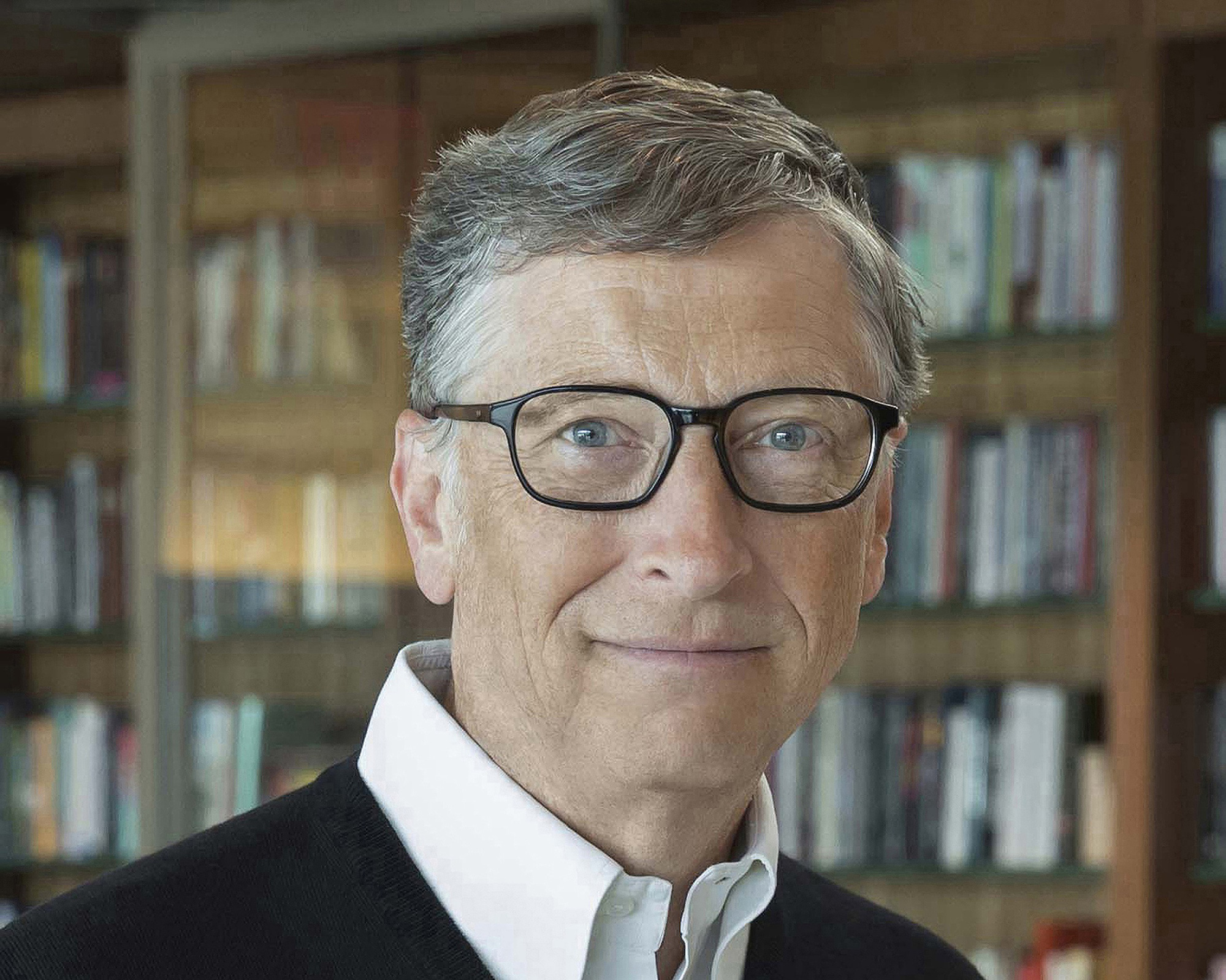

Gates, a vocal advocate for climate solutions through innovation, has expressed interest in technologies that can serve as emergency brakes should carbon mitigation efforts fall short. His funding of the Harvard team signals both a sense of urgency and a willingness to explore unorthodox strategies.

The proposed experiment involves a small-scale test flight that would release a limited amount of material at high altitude to study its dispersion, reflectivity, and potential interactions with atmospheric chemistry.

The initial focus is on calcium carbonate—a compound believed to pose fewer environmental risks than sulfur dioxide, which is associated with acid rain.

Researchers aim to measure how these particles behave in real-world conditions, gather data on potential side effects, and assess the feasibility of scaling up. The test is not designed to trigger any measurable cooling but rather to validate the underlying models and mechanisms.

However, the initiative has drawn criticism from environmental groups, ethicists, and even some climate scientists. Opponents argue that geoengineering represents a dangerous path that distracts from the urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

They warn that technological fixes like this could create a moral hazard, giving governments and corporations an excuse to delay meaningful decarbonization.

Others point to the unpredictable consequences of manipulating the climate system, including regional weather disruptions, ozone depletion, or geopolitical disputes over the governance of a shared atmosphere.

Critics also question the legitimacy of private individuals, even philanthropists like Gates, wielding influence over global-scale environmental interventions.

Despite these concerns, proponents argue that geoengineering deserves careful consideration as part of a broader climate risk management strategy.

They point out that even with aggressive emissions cuts, global temperatures are on track to exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—a threshold associated with severe ecological and social disruptions.

In that context, solar geoengineering could serve as a temporary measure to reduce peak temperatures, prevent ice sheet collapse, or slow the pace of climate-related disasters.

Gates himself has framed the project as a “last resort” rather than a primary solution, and he emphasizes the importance of transparency, governance, and scientific rigor in its development.

The debate also touches on questions of equity and justice. Developing nations, which are often the most vulnerable to climate impacts, have expressed skepticism about geoengineering experiments conducted by wealthy countries or individuals.

They fear being left out of decision-making processes that could affect their weather patterns, food security, or water availability. Some international organizations have called for a moratorium on outdoor geoengineering tests until a global regulatory framework is established.

The Harvard team has responded by engaging with stakeholders, holding public forums, and publishing detailed risk assessments, but the concerns remain potent.

The science behind solar geoengineering is still in its early stages, and there are numerous uncertainties to resolve. Key questions include how long the particles would remain suspended, whether they could drift and concentrate in unintended regions, and how they might interact with cloud formation, precipitation, or air circulation.

There is also the issue of “termination shock”—a scenario in which the sudden cessation of aerosol injections could lead to rapid warming if greenhouse gas concentrations remain high. This underscores the importance of coupling any geoengineering effort with continued emissions reductions and carbon removal strategies.

Gates’s involvement in the project has added visibility and credibility, but it has also intensified scrutiny. As one of the most influential voices in climate philanthropy, Gates has invested in a wide array of technologies, from advanced nuclear reactors and direct air capture to low-carbon cement and lab-grown meat.

His approach emphasizes technological innovation as a complement to policy and behavioral change. However, critics argue that focusing too heavily on tech fixes risks underestimating the importance of systemic shifts in energy, agriculture, and consumption.

The chemical cloud project, in particular, has become a lightning rod for this broader tension between innovation and mitigation.

From a policy perspective, the emergence of solar geoengineering raises thorny issues about international law, oversight, and enforcement. Unlike emissions reduction targets, which can be negotiated and monitored through treaties, geoengineering affects the entire planet and lacks clear mechanisms for consent or accountability.

Who gets to decide when, where, and how to deploy such technologies? What happens if one nation opposes a program initiated by another? These questions remain unresolved, and they highlight the urgent need for multilateral dialogue before any large-scale experiments are undertaken.

In recent months, global institutions such as the United Nations Environment Programme and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have begun to acknowledge the growing interest in geoengineering and the need for research governance.

Some scientists advocate for the establishment of a dedicated international body to coordinate research, set ethical standards, and ensure that experimentation is conducted in a transparent and inclusive manner.

Others call for a cautious moratorium until more is known. The Harvard team, with Gates’s backing, may end up setting the precedent by which future efforts are judged.

As the climate crisis deepens and traditional solutions struggle to keep pace, the appeal of geoengineering will likely grow. The promise of a controllable, scalable mechanism to cool the planet is seductive—but it is also fraught with uncertainty.

For now, the chemical cloud project remains a research effort, not a deployment plan. But its existence signals a new phase in humanity’s relationship with the environment: one where the power to alter the climate lies not just in fossil fuels, but in our capacity to intervene intentionally.

Bill Gates has never shied away from controversial ideas. His foundation has reshaped global health, his investments have reshaped energy discourse, and now, his interest in geoengineering may reshape how we think about the boundaries of science, ethics, and climate action.

Whether history will judge this effort as visionary or reckless remains to be seen. What is certain is that the conversation has changed. Climate change is no longer just about emissions—it is about decisions. And the question facing the world now is not just how to stop global warming, but how far we are willing to go to do it.

-1749614885-q80.webp)

-1751806048-q80.webp)