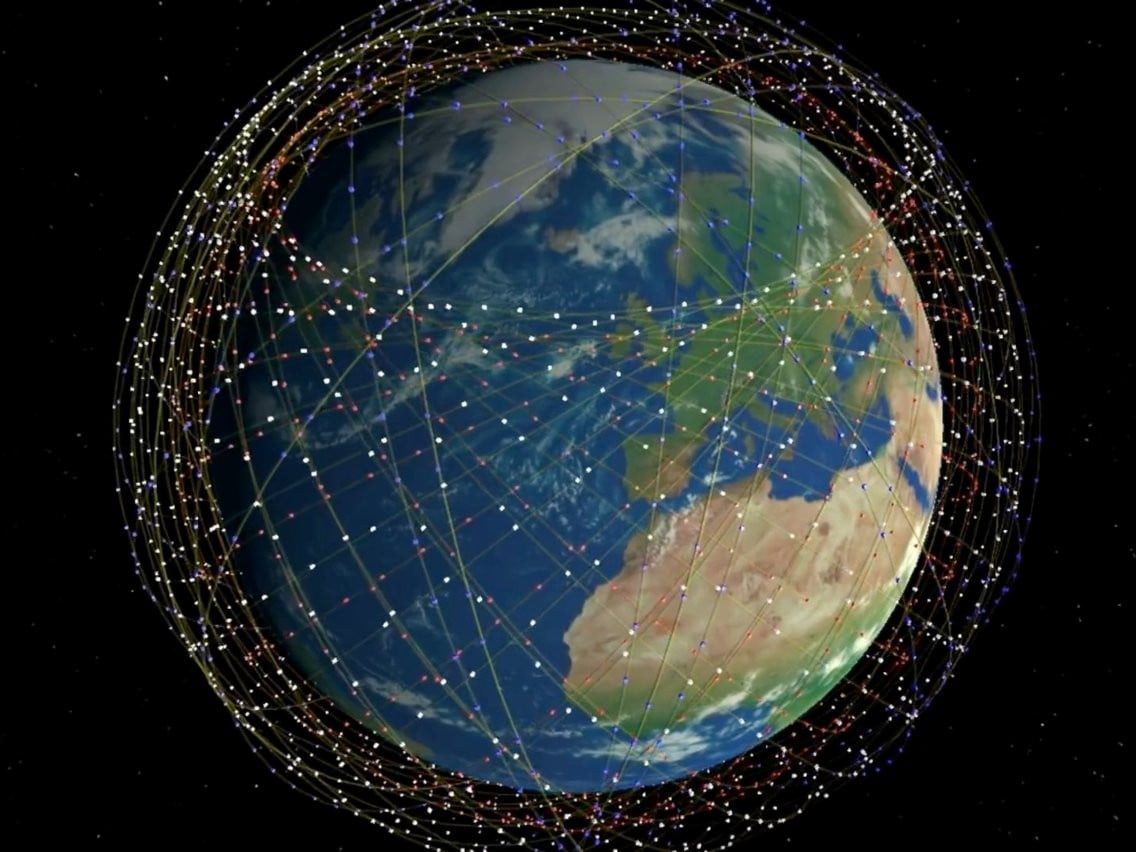

When Elon Musk’s Starlink launched a bold initiative to blanket the world with high-speed internet from space, it was heralded as a game-changer for the unconnected and underserved.

By deploying a vast constellation of low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, Starlink promised to eliminate the digital divide — not just narrow it. And nowhere was this promise more alluring than in Mexico.

Armed with a plan valued at over $430 million, Starlink set out to connect some of Mexico’s most remote and rural regions — communities often overlooked by traditional telecoms due to terrain, distance, or cost inefficiency.

It was a mission that seemed tailor-made for the company's strengths: bypassing ground infrastructure by shooting connectivity straight from the sky.

But now, several years and over 1.6 million users later, Starlink’s Mexican venture is facing a quietly growing problem: the missing link between satellites in space and people on the ground.

Despite the dollars, despite the orbiting hardware, and despite the impressive subscriber numbers, the project’s reach has started to stall — not because of the technology, but because of something far more mundane: infrastructure, affordability, and policy friction.

Starlink's operating model is simple in concept, yet revolutionary in execution. Thousands of LEO satellites beam internet signals across vast swaths of the Earth’s surface. In return, end-users need only a satellite dish (the “user terminal”), a modem, and power.

In regions like rural Mexico, this model could be transformative. Many of these communities lack the economic incentive for traditional telecoms to invest in ground infrastructure — running fiber or cellular towers can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per village. Starlink’s aerial approach offers to leapfrog over those barriers.

It’s an idea Mexico embraced eagerly. In early government partnerships, authorities praised the project as a solution to the country’s digital inequality.

Communities that had long gone without reliable internet suddenly saw the promise of streaming classes, telemedicine, and economic opportunities.

And indeed, over 1.6 million users have already connected through Starlink — a number that suggests early success. But beneath that surface, problems are emerging.

Starlink’s Achilles’ heel is not in space — it’s on Earth. The $430 million plan appears to have underestimated a crucial piece of the puzzle: the scale and logistics of deploying user terminals on the ground.

Each connection requires a small but essential kit: a satellite dish, modem, power source, and installation. For an urban user with disposable income and access to electricity, this is a minor hurdle. For a remote community in Chiapas or Oaxaca, it’s often a dealbreaker.

While some Mexican government programs subsidized access to Starlink kits, there simply weren’t enough to go around. In many villages, only schools or town centers were equipped — not individual households.

And even in areas where terminals were delivered, latency issues and unreliable service have been reported due to the high demand and limited ground support infrastructure.

It’s a classic case of a brilliant technology colliding with real-world friction: topography, policy, logistics, and cost.

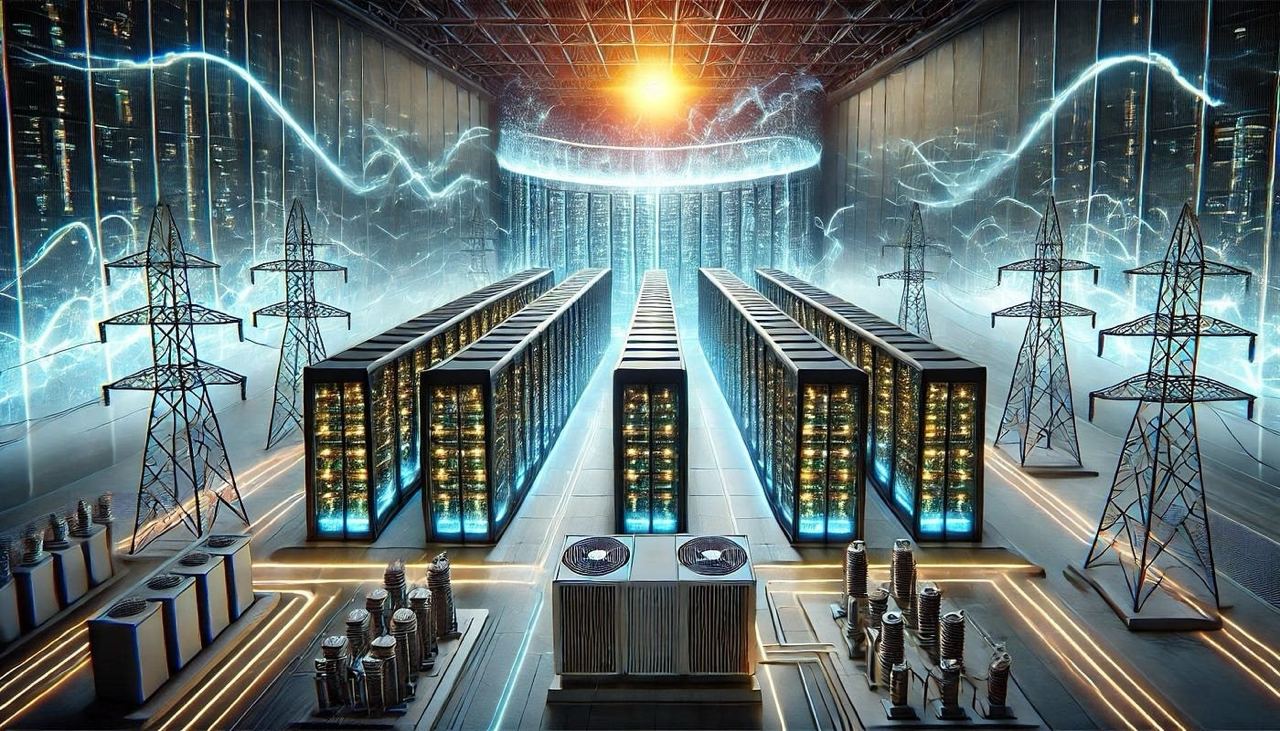

One might think that satellite internet is the ideal solution precisely because it avoids conventional infrastructure. But the reality is more nuanced.

Satellite systems like Starlink still depend on substantial ground support. Gateways (large ground stations that connect satellites to the wider internet), user terminals, trained technicians, power solutions — all these are physical bottlenecks. Without them, the satellites might as well be stars in the sky: beautiful, distant, and unreachable.

In Mexico, several planned ground stations were delayed due to regulatory red tape. Local policies, bureaucratic approval processes, and even land ownership issues have slowed expansion. Unlike the clean, scalable logic of software, infrastructure is messy, political, and slow.

Moreover, Mexico's patchy electrical grid in rural areas means that even where terminals are deployed, connectivity can be erratic. No power = no internet. It's a sobering reminder that high-tech innovation can only move as fast as the slowest component in the system.

At the heart of the challenge lies a simple, brutal truth: the people who most need Starlink can’t always afford it.

A Starlink terminal costs around $400–600 USD, with a monthly subscription fee of $50–100 USD. For families living on subsistence agriculture or informal labor wages, this is an impossible ask.

In a country where the minimum wage is less than $15 a day, this level of pricing is exclusionary by default.

This has created an awkward disconnect. Starlink’s technology is aimed at remote communities, but its business model fits urban early adopters. The very people it's meant to liberate digitally are being priced out of the revolution.

Even with government subsidies and international support, the math doesn’t add up. The cost of full rural deployment across all underserved areas in Mexico would run into the billions — well beyond the current $430 million scope.

What’s unfolding in Mexico is not a failure of vision. It’s a case study in the limits of technology when decoupled from systems thinking.

Starlink is not a bad solution. In fact, it’s arguably one of the best tools ever created for connecting difficult terrain. But like all tools, it needs the right context to work.

That means local partnerships, affordability models, cultural adaptation, and a hybrid approach that mixes satellite with terrestrial infrastructure.

Ironically, the very feature that made Starlink attractive — its independence from traditional telecom models — may be its weakest point in reaching true scale. No single company, not even one with Elon Musk’s ambition and resources, can solve systemic connectivity on its own.

The future of Starlink in Mexico is far from doomed. The system is still expanding, and public-private partnerships may yet close the gap between orbital capacity and ground-level access.

Educational programs, healthcare networks, and emergency response units stand to benefit enormously from satellite connectivity.

But the initial enthusiasm must now give way to practical, long-term planning. Starlink is not a silver bullet — it’s a platform. And like any platform, its value depends on the ecosystem built around it.

If Mexico — and other nations with similar geographies — are to benefit fully from satellite internet, then investments in energy, local support networks, and pricing models must rise to meet the promise floating above them.

The Starlink project in Mexico is a perfect parable for the 21st-century tech era: sky-high ambition, astronomical investment, and genuine innovation — all threatened by the gravity of human systems.

It’s not enough to put $430 million worth of hardware in the sky.

It has to land.

And landing means local alignment, boots on the ground, and an honest reckoning with the messy world beneath the satellites.

-1747901184-q80.webp)