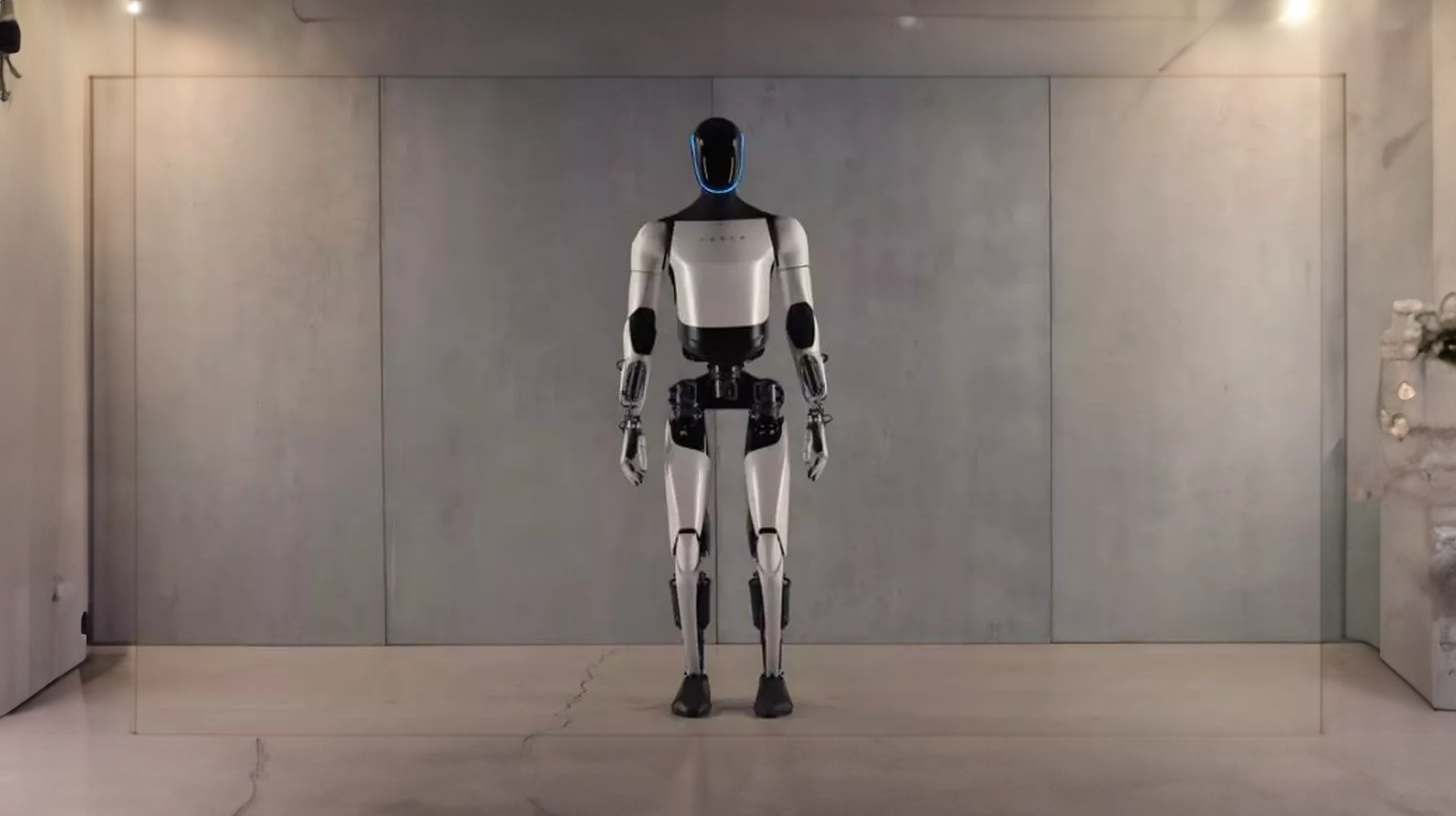

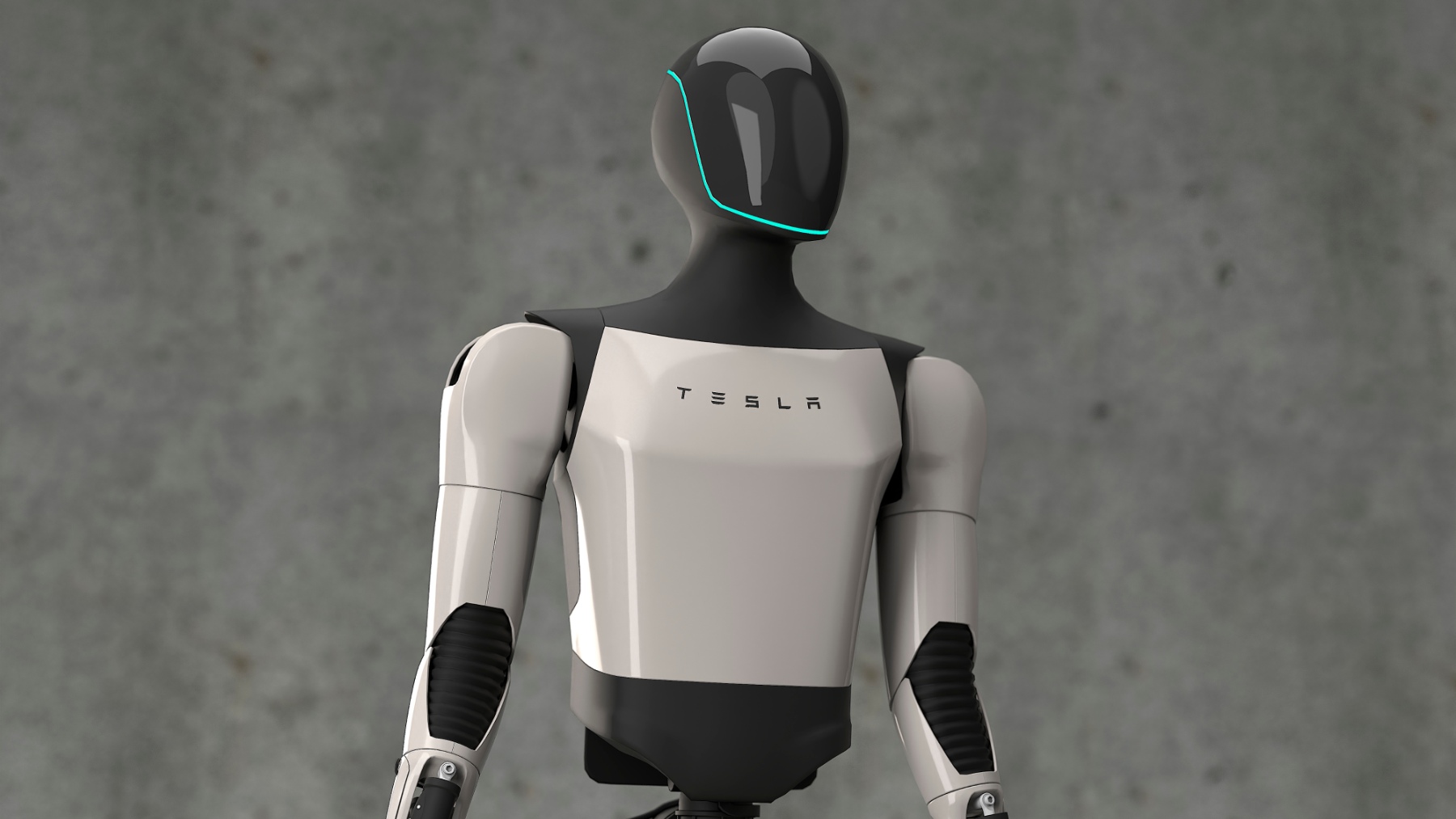

Tesla’s grand vision of building humanoid robots for just $20,000 is now facing a harsh reality check. As the U.S.-China trade war escalates and tariffs skyrocket, the technological dream championed by Elon Musk could be on the verge of unraveling.

The promise of mass-producing the Optimus robot, a general-purpose humanoid meant to revolutionize labor, may be far more dependent on Beijing than Silicon Valley is willing to admit. Experts warn that without access to China’s deeply integrated and low-cost manufacturing ecosystem, Musk’s vision could go from futuristic to financially infeasible.

Behind the gleaming ambition of Optimus lies a network of high-precision hardware parts—actuators, motors, joints, sensors—that form the robot’s skeleton and nervous system. And that network runs straight through China. According to Xu Xuecheng, lead scientist of the Zhejiang Humanoid Robot Innovation Centre, many of these components are already being sourced heavily from Chinese manufacturers.

While current imports remain modest due to early-stage development, Xu predicts that as production scales, dependence on China will intensify. "Tesla’s mass-production plan for Optimus is likely to be put on hold,” he warned bluntly, pointing to rising costs and trade barriers that could sabotage Tesla’s aggressive pricing strategy.

That strategy hinges on one number: $20,000. It’s a figure Musk has reiterated publicly, suggesting Tesla could eventually produce over 1 million units per year at that cost. But industry veterans argue that this goal only makes sense if Tesla continues to rely on the Chinese supply chain. “Without the Chinese supply chain, the cost on their end would likely be at least 50 per cent higher,” said He Liang, founder and chairman of Yunmu Intelligent Manufacturing in Suzhou.

His company, which is also racing to commercialize humanoid robots, estimates that two-thirds of Optimus’ core components come from China. Motors alone account for roughly half of the hardware costs, with robotic hands contributing another 10 percent. And China currently dominates both categories in volume and affordability.

The question, then, is not whether Tesla can build a humanoid robot. The question is whether it can build one affordably without China. And the answer, by most accounts, is a resounding no.

Tesla’s Optimus project is often described as a disruptive force—a “catfish” that will stir up stagnant waters in the robotics sector. But to disrupt the industry, it must first survive its own production reality.

Lu Hancheng, director of the Gaogong Robot Industry Research Institute, explains that the real disruption begins when both software and hardware converge at scale. That, he says, is when China’s role becomes indispensable. “In China, you can source all of the necessary components in one place – that level of supply-chain integration simply doesn’t exist elsewhere.”

This isn’t just about price. It’s about speed, logistics, and the completeness of China’s ecosystem. From raw materials to finished parts, Chinese suppliers operate in a tightly connected industrial web that allows rapid iteration and scaling—key ingredients for bringing down costs and accelerating deployment.

While Chinese components may still lag behind European or Japanese parts in premium quality, experts stress that for Tesla’s purposes, they are “good enough”—especially when viewed through the lens of affordability and mass production.

Yet geopolitical friction threatens to tear this web apart. The Trump administration, now in its second term, has intensified the trade war, pushing tariffs on Chinese imports.

These aggressive trade measures have been justified as part of a broader strategy to decouple the U.S. from Chinese influence, especially in strategic technologies. But in doing so, Washington may be destabilizing its own innovation pipeline—one that Elon Musk and Tesla heavily depend on.

Ironically, while the U.S. government talks about reshoring supply chains and promoting domestic manufacturing, it is Tesla, one of the country’s flagship innovators, that finds itself caught in the crosshairs. Elon Musk has long positioned Optimus as a labor-saving solution for industries ranging from manufacturing to home care.

A robot for every factory, every warehouse, and possibly even every household. But without affordable components, that vision collapses into a luxury novelty, not a mass-market tool.

It’s not just Tesla facing this squeeze. Other humanoid robot makers, including California-based Figure and China’s own Yunmu, are feeling the pressure. Yunmu, for example, expects to manufacture up to 1,000 humanoid units this year, targeting commercial applications in tourism, service industries, and research.

Despite local sourcing for many components, even Yunmu faces exposure to U.S.-China friction due to its need for certain American chips and computing modules. The tension cuts both ways, and it could slow global progress in humanoid robotics just as the sector is gaining momentum.

Still, the bulk of dependency flows from the West to China, not the other way around. As He Liang explains, while China still imports some high-end components, most parts for its domestic robots are either made locally or have viable alternatives.

In contrast, U.S. firms have few places to turn if Chinese supplies are cut off. Replacing China’s manufacturing depth would take years—if not decades—to replicate elsewhere.

The implications are profound. Tesla’s Optimus robot has been pitched not just as a product, but as the cornerstone of a future where robots take over mundane or dangerous jobs. Musk has even suggested that Optimus could be “more important than the car business” over the long run.

But all of that depends on reaching cost parity with human labor, or at least coming close. Every $1,000 increase in cost moves that dream further out of reach.

As it stands now, the $20,000 robot is more than a technological feat—it’s a geopolitical bargaining chip. And Musk, for all his rhetoric about American exceptionalism and self-reliance, may find himself kneeling at the altar of Chinese manufacturing, at least if he wants his robot army to materialize.

The bitter irony is that even as the U.S. imposes crippling tariffs on Chinese goods in the name of economic security, it may be hobbling its most ambitious companies in the process. If Optimus stalls, it won’t be due to a lack of vision or engineering. It will be because geopolitics trumped practicality.

Tesla’s robotics roadmap remains ambitious. But for now, the future of its humanoid dream may lie not in the hands of American engineers, but in the factories of Ningbo, Shenzhen, and Suzhou. Until Washington and Beijing find a new equilibrium—or until another country miraculously replicates China’s supply chain magic—the $20,000 Optimus may remain just that: a dream.

-1749483799-q80.webp)

-1747904625-q80.webp)

-1747734794-q80.webp)