What if you were told that in just a few years, working only two or three days a week could secure a decent living for you and your family? That prospect might make you jump for joy at the thought of more leisure and less toil.

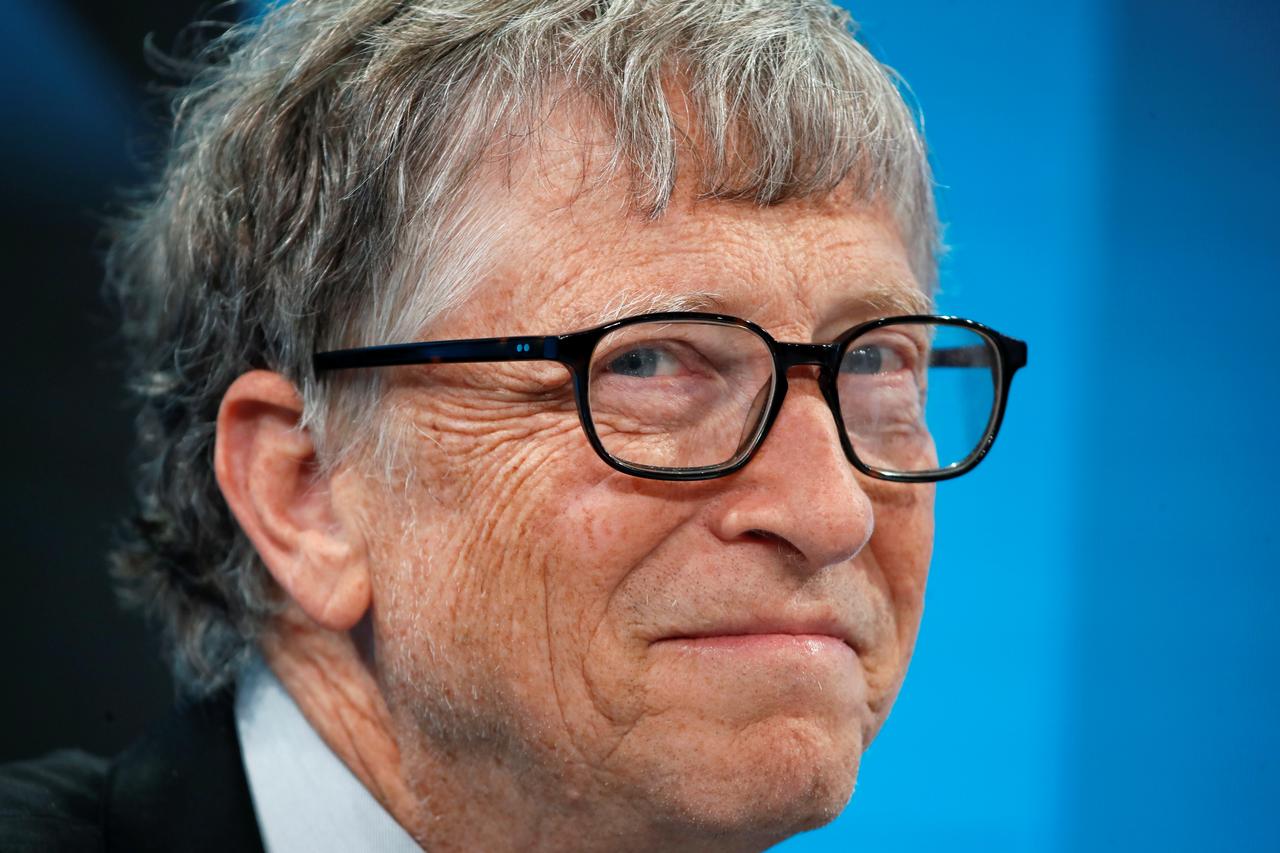

This idea has recently gained attention thanks to Bill Gates, who in promoting his new memoir, Source Code, on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon suggested that artificial intelligence could make such a future possible within a decade.

Gates mused that humans might no longer be needed "for most things," raising the question of whether people would then only need to work two or three days a week.

If you feel overworked and pressed for time now, this notion offers a hopeful glimpse of a future with more free time and less stress.

However, as enticing as this sounds, psychological research points to a less straightforward reality: humans derive substantial benefit from hard work, and a sudden life of ease might pose unexpected challenges to our well-being and sense of purpose.

This tension between leisure and effort reminded me of an insightful article by Alex Hutchinson in The Atlantic, which explores the curious phenomenon of why so many non-elite, non-professional athletes participate in grueling endurance events such as marathons.

At face value, this behavior seems contradictory to our instinctual desire for comfort since these events are physically demanding, painful, and expensive.

Why would humans willingly seek out such hardship when we are, after all, creatures naturally inclined toward comfort and avoidance of pain? Hutchinson’s analysis reveals that this paradox, often called the “effort paradox,” taps into a fundamental aspect of human psychology: people find inherent value and satisfaction in exerting effort and overcoming challenges, even when such effort is not strictly necessary for survival.

Studies support this idea, showing that people tend to value things they have put effort into more than those that come easily.

For example, one research experiment found that individuals preferred an Ikea-style table they assembled themselves over an identical pre-assembled table, simply because of the effort invested.

Similarly, children are observed to find more enjoyment in games that are harder and require more skill, rather than those that are trivially easy.

This inclination extends to activities such as running marathons, where despite the physical discomfort, participants report a deep sense of achievement and personal satisfaction. The process of struggling, pushing limits, and ultimately mastering a difficult task fulfills psychological needs that mere comfort cannot.

Why does effort feel so rewarding? Hutchinson points to research indicating that a “sweet spot” exists where effort is challenging but manageable, producing a pleasurable sense of mastery and meaning.

This optimal level of difficulty is critical because it allows individuals to feel competent and engaged without becoming overwhelmed. The sense of meaning derived from such challenges is crucial to human happiness and fulfillment.

Indeed, many eminent psychologists argue that feeling one’s life is meaningful and purposeful is even more important for well-being than transient pleasures or happiness. The pursuit and achievement of meaningful goals, often requiring hard work, gives life its richness and depth.

Elizabeth Bonawitz, a Harvard psychologist, explains to Hutchinson that hard work is perhaps the key path by which people satisfy essential needs such as competence, mastery, and even self-understanding.

These psychological fulfillments cannot be attained without exertion; they require individuals to push themselves beyond their comfort zones and develop new skills. The struggle itself becomes a vital component of personal growth and happiness. Without these challenges, life risks becoming hollow and aimless.

This understanding brings us back to Bill Gates’s prediction about AI and a future where humans might work drastically fewer hours because intelligent machines take over most tasks.

While some may fear that AI will displace jobs and create social upheaval, Gates’s vision of a two- or three-day workweek raises another question: If technology makes life significantly easier, would humans thrive or struggle with the abundance of free time? The answer may be more complicated than simple relief from labor.

On one hand, AI’s promise to cure diseases, automate tedious chores, and enhance productivity offers undeniable benefits. A future where robots handle cleaning, cooking, childcare, and even mental health support sounds like a dream come true.

Former Facebook executive Julie Zhou recently reflected on this prospect in a thoughtful essay on Medium. She imagines AI therapists providing precisely the emotional support people crave and AI creating customized films perfectly tailored to individual tastes.

This vision paints a world of unprecedented comfort and convenience, seemingly eliminating many sources of stress and hardship.

Yet, Zhou also cautions that comfort alone will not guarantee happiness or fulfillment. She argues that the time freed up by AI must be spent engaging in voluntary, meaningful challenges rather than mere passive leisure.

She calls for a pursuit of “voluntary challenge,” emphasizing that true satisfaction comes not from easy pleasures or quick dopamine hits but from activities that require effort and personal growth.

Paradoxically, doing hard things makes people happier and better equipped to enjoy life. Struggle, in this sense, is not merely a burden but a source of resilience and deeper joy.

This perspective echoes the concerns of many psychologists and social thinkers who worry that a world without challenges might lead to ennui, depression, and loss of purpose. Just as retirees who dream of endless leisure sometimes find themselves lonely and aimless, a society where work and difficulty vanish could face psychological pitfalls.

Humans appear wired to seek meaning through effort, mastery, and achievement. If AI creates a world of ease, individuals may need to invent new ways to challenge themselves to preserve their sense of purpose.

Entrepreneurs and leaders watching the AI revolution unfold should therefore consider the implications carefully. While ending human suffering and want is unquestionably good, the unintended consequences of an ultra-convenient life should not be ignored. It may be necessary to rethink what “work” means and how people derive value and identity from their efforts.

Gates’s prediction of a two-day workweek is inspiring but also demands deeper reflection on how society will fill the rest of the week meaningfully.

In summary, as AI advances and promises to transform the nature of labor and leisure, humans will face profound questions about purpose and fulfillment.

The psychological evidence suggests that hard work, challenge, and mastery are central to human happiness. If robots make life significantly easier, people will need to find new challenges—whether through sports, art, learning, or other endeavors—to maintain a sense of meaning.

The future may hold unprecedented comfort, but also a need to cultivate resilience and voluntary challenge to thrive emotionally and psychologically. Ultimately, while AI can transform work, how humans choose to engage with life’s challenges will determine their happiness and well-being.

-1745208039-q80.webp)

-1746080170-q80.webp)

-1743734782-q80.webp)

-1745481254-q80.webp)